When asked what draws him to a given story or work, Marvel and DC comic writer Greg Pak quickly dismisses the merit ascribed to a work by a “Best Of” list. “People come out with lists of the ‘Greatest Films Ever Made’ and all that,” he muses, “and I think that’s just entirely subjective. A film that may be just a film to somebody else may be the formative film of your life.”

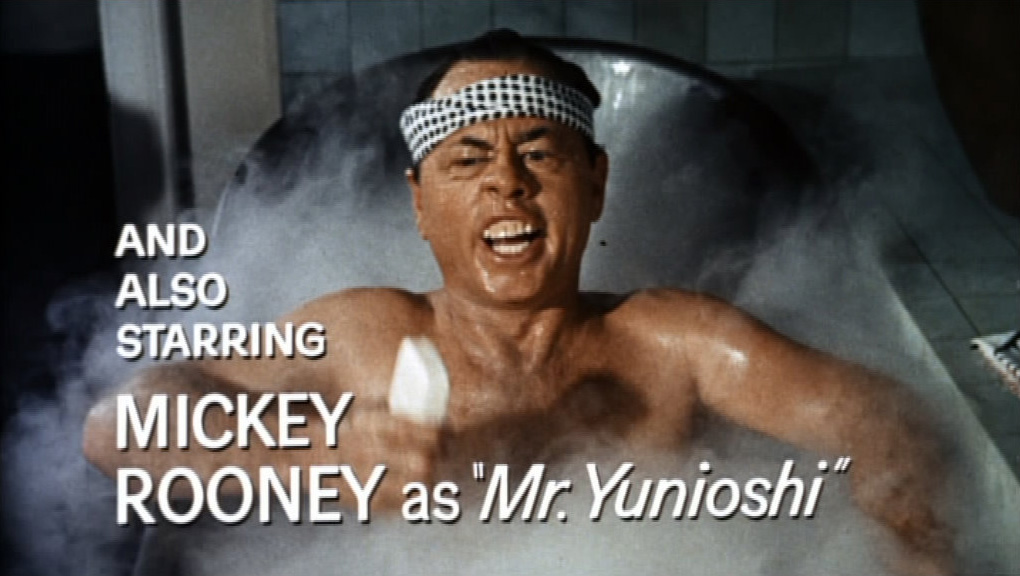

For Pak, those works included classic black and white films (he loved the “aesthetic”), Westerns, and outdoor adventure stories (he was Boy Scout). Pak is also especially drawn to work that reflected his experiences, or at least had similarities to them. “I paid a lot of attention whenever I was able to see non-stereotypical depictions or multi-dimensional depictions of Asian people.”

For Pak, those works included classic black and white films (he loved the “aesthetic”), Westerns, and outdoor adventure stories (he was Boy Scout). Pak is also especially drawn to work that reflected his experiences, or at least had similarities to them. “I paid a lot of attention whenever I was able to see non-stereotypical depictions or multi-dimensional depictions of Asian people.”

Pak’s latest and entirely creator-owned work, Kingsway West, serves a testament to this notion. The comic, released August 24, 2016, follows the narrative of a Chinese gunslinger as he treks throughout a magical Old West to find his wife. Pak uses his prowess for fantasy storytelling to give fantastical dimension to the world where Kingsway West takes place. Combining fantasy elements–particularly, the presence of a substance called “red gold” in the world of Kingsway West–with the largely looked-over history of Chinese people in the Old West allows Pak “to not worry to be beholden to actual American history… Instead, I can actually create a new anthology which plays with all the same themes that I was gonna play with before.”

Kingsway West goes back in time in more ways than one: Pak conceptualized the story over 20 years ago. “It’s a story that made a lot of sense to me because I’m an Asian-American kid who grew up in Texas. I loved Westerns, and [when] I learned about the actual history of Chinese and the Old West… my head exploded.”

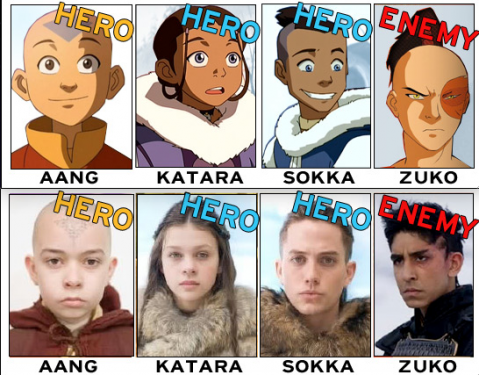

So why now, and not 20 years ago? “I wanted to make Kingsway West as a feature film way back when, and that didn’t happen–one, because it’s a Western, and two, because it’s a story with Chinese and Mexican leads. At that time, I think it was hard [for] financiers to get it.”

“When I was growing up, I had that Margaret Cho experience,” he continues, “Where you’d be like, ‘Asian person on TV!’ It’d be such a shocking, unusual thing. It was a big deal. And usually, it was some embarrassing racist stereotype.”

But even though there’s still much progress to be made, Pak notes that times have undoubtedly changed. “You’re starting to see it happen all over the place… Fresh Off the Boat and all those shows that have gotten green-lit recently is due to really, really hard work by really, really dedicated writers and producers. But it’s also [because] we’re getting closer to the point where it’s a no-brainer… the business people will realize that there’s money to be made by making stories with people of color as leads.”

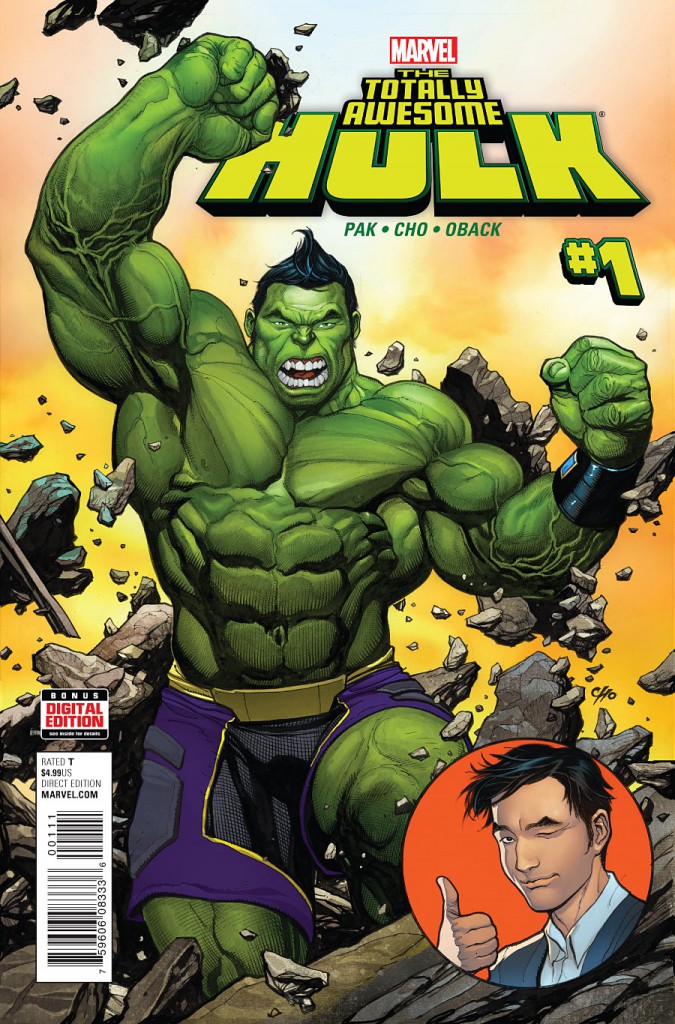

Pak also notes that the comic industry is extremely different from the film industry because comics are “willing to take more risks.” Pak remarks, “I’ve literally never had anybody ask me if I could change the ethnicity of characters in stories I’ve pitched in the comics world.” This shows in Pak’s creation of the Korean-American character, Amadeus Cho, who recently inherited Bruce Banner’s powers to become the Totally Awesome Hulk. “At no stage during the entire process [of the creation of Amadeus] did anyone say, ‘Does he have to be Asian?’ [That] would have happened in the film industry at that time.”

While it’s easy to simply hope for the film industry to follow the comic industry’s lead in showcasing more diverse–and more reflective–stories, Pak urges aspiring creators to “devote yourself [to the story] that means the most in your heart. If you have a story and nobody else gets it, but you know that’s the story you have to tell, keep working on it until people can get it.”

For more information about Kingsway West and how you can place an order, visit kingswaywest.com.

![]()

Images via Greg Pak & Marvel